This should have been two topics, but I just went with it.

- Window Tax

- The Long S

Window Tax

I happened across a YouTube video of an old house built in the UK. It looks as though the building was either of Georgian or Victorian periods, but upon going through the building, it’s likely that it was built in the late 1600’s given the bricking of several windows to avoid the Window Tax that existed in the UK between 1696 and 1851.

Everything is remarkable about this house from the limecrete floors through to the large beams throughout the house, as well as the utilisation of all space in the roof area. Not to forget the old doors. The YouTuber in this video is very fascinated by the doors. There’s a good reason to be when you consider they’re 400 plus years old.

If you haven’t followed the Window Tax link above, a brief history is outlined here:

- Coin Clipping was a major problem in the 1600’s where it was considered high treason and punishable by death.

- As a counter measure to coin clipping, King William III introduced a Window Tax in 1696.

- To get around the tax many premises boarded up windows.

- It was a varying rate depending on how many windows the premises had.

- It was repealed in 1851 after pressure from doctors and others who argued that lack of light was a source of ill health.

- The same tax was imposed in France in 1798 and only repealed in 1926!

- The tax was designed to “tax the relative prosperity of the taxpayer, but without the controversy that surrounded the idea of income tax” (wiki).

The Long S

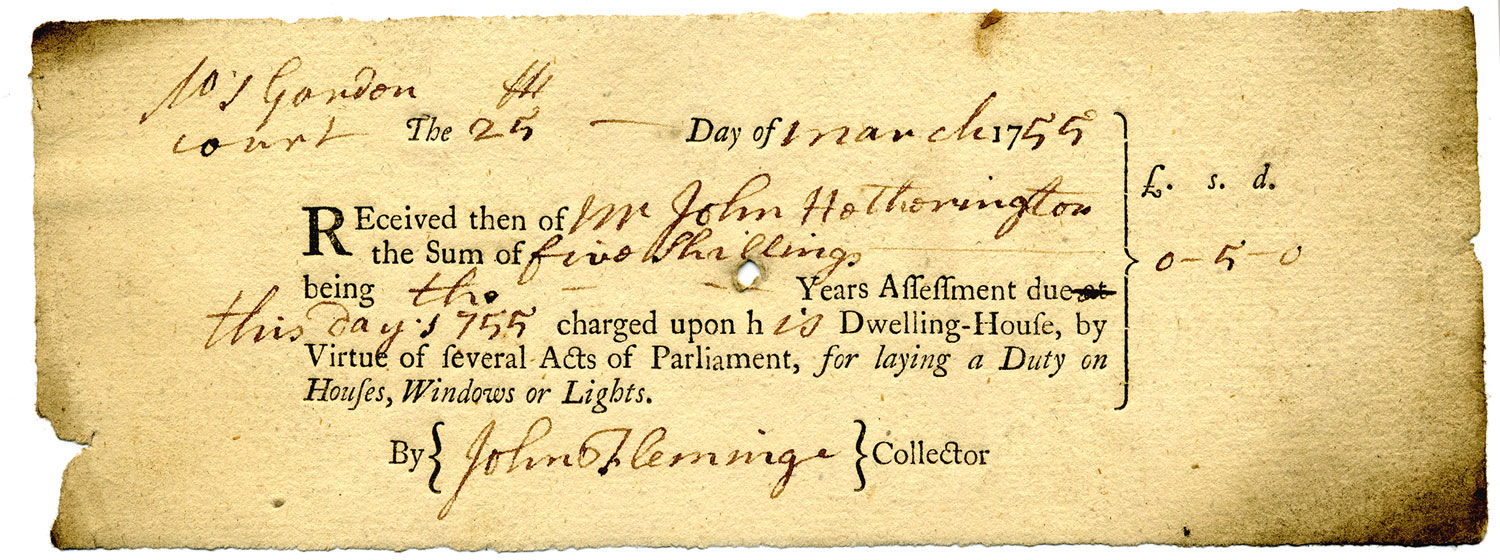

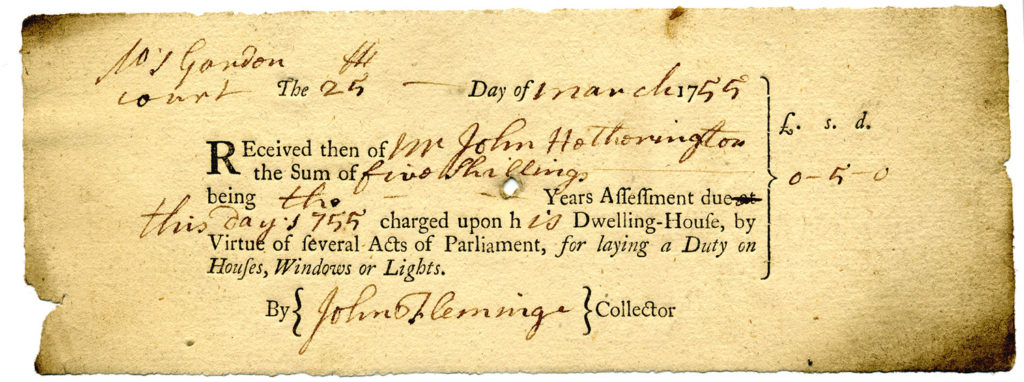

A couple of other side notes from this are detailed in the tax receipt below (click for a larger version):

I am reminded of a conversation I had with my grandmother many decades ago, we were talking about currency and she asked me “What does L.S.D. stand for?” I don’t think I had an idea of the drug at the time, but she continued with, “Pounds, shillings, and pence.” The abbreviation can be seen to the right of the receipt.

I am also reminded of some very early (pre Sydney Morning Herald) Sydney Gazette archival books we had at our school library in the 1980s. I remember reading though them being amazed at the language, but especially the type.

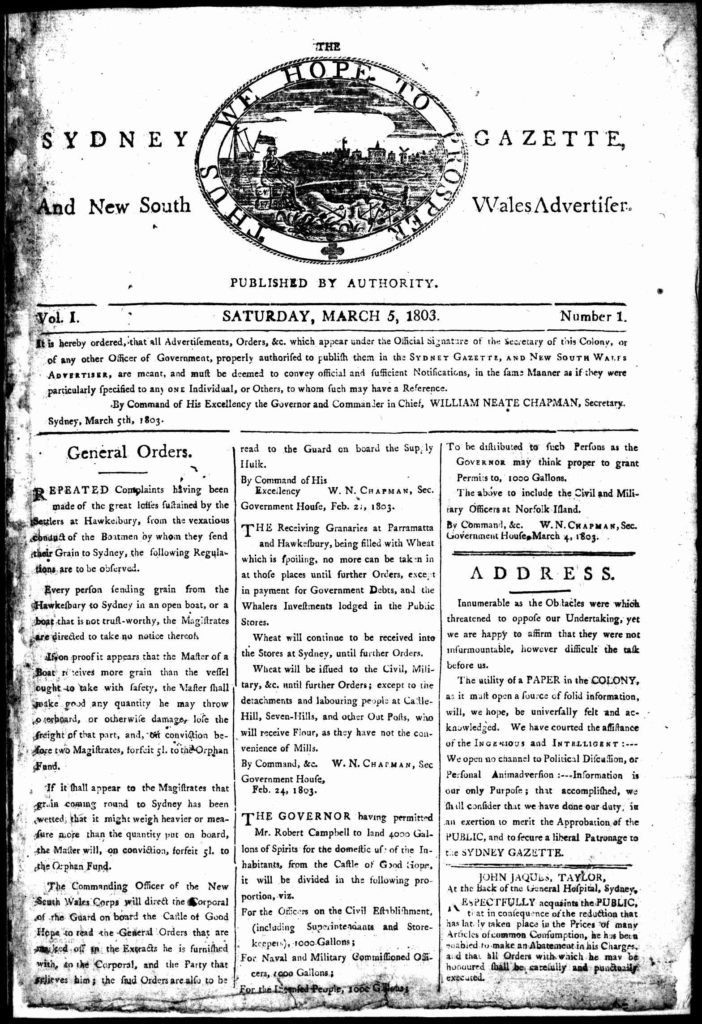

This one took some searching because I had mistakenly thought I was looking for archival Sydney Morning Herald material. It turns out I was looking for material from the Sydney Gazette. The first publication in Australia, running from 1803 to 1842. It was the official paper of the New South Wales government. Under the editorship of Robert Howe in 1824, it ceased to be censored by the colonial government. (This is pre-federation of the states in 1901).

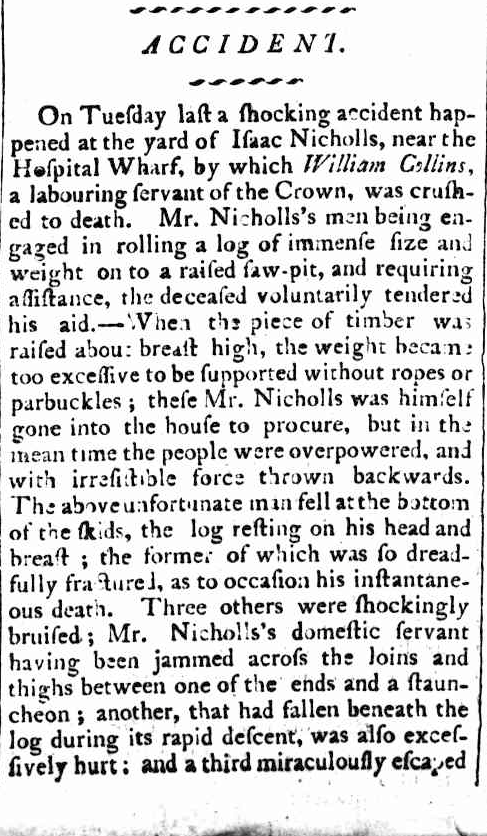

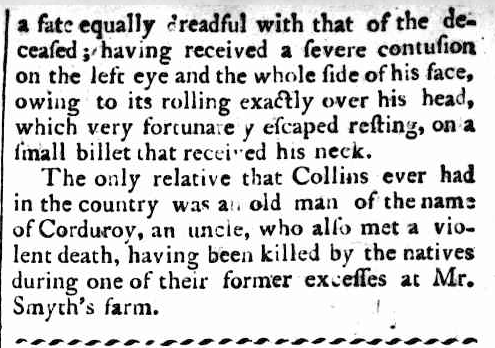

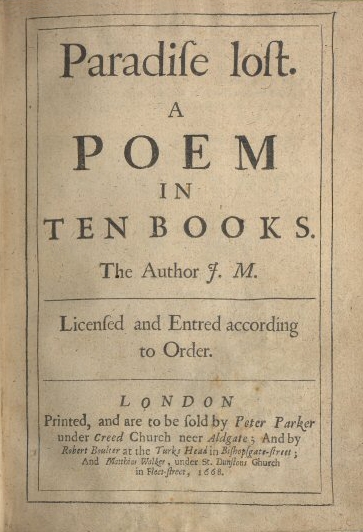

When a non-capital ‘s’ was present in a word, not being the last letter, it was typed as a form of ‘f’. The exact character varies according to being normalised or italics or even handwritten, but several forms are exhibited below. In normal text is appears as an “f” without the cross bar: “ſ”. In italics, it appeared more like the integral character of mathematics: “∫”

Examples: “ſinfulneſs” for “sinfulness” and “ſucceſsful” for “successful”.

It wasn’t until many years later with the advent of the internet, I found this to be what is known as the “Long S“, or in more modern times, the “short”, “terminal” or “round” s.

Here is the first page of the Sydney Gazette:

Some other examples from the Sydney Gazette and elsewhere from the Internet:

BTW, I do LOVE the lower case “c”, it’s just the long S does take the limelight.

In the original penned documents of the USA founding, in the Declaration of Independence (1776) can be seen the mid-18th century practice of extensive use of long-s, and in the Constitution (1789) can be seen the late 18th century practice of using long-s only as the first member of a double-S combination. You can search such documents with Google image search (images.google.com) and you’ll see several typefaces along with some images of the original handwritten source.